So I think many people, in some way, have read or at least heard about The Psychology of Money. In that book, Morgan Housel says something very important: a person should know what is “enough“.

He explains it with a simple example — you can eat more and more, but if you don’t stop at the right point, later it will only make you uncomfortable or sick. Knowing when to stop matters.

When I look at payment apps, food delivery apps, and quick commerce platforms, I feel the same thing applies here. They don’t seem to know when to stop — and that is hurting almost every stakeholder: sellers and suppliers, employees, banks, customers, and even the government.

In the beginning phase, everything looks fine. Growth is fast, users are happy, discounts are everywhere. But the problem starts later.

Let me explain with examples — not the full picture, just a glimpse.

The payment app: useful, but limited in value creation

Payment apps have done something important:

- digitised transactions,

- improved compliance,

- helped regulation and traceability.

- Collect the data like preferences of customer for good purposes.

That matters.

But at their core, they are middlemen between:

- customers,

- banks,

- and the government payment rails.

The question worth asking is simple:

Beyond convenience, are payment apps creating unique, long-term value for users — or are they mostly a preference layer built on existing systems?

Charging a small, transparent fee is fine.

But by themselves, payment apps don’t fundamentally reduce the cost of living or doing business.

Keep this thought — it matters later.

Food delivery apps

In my opinion, this is where things become worst — for customers, sellers, banks, and delivery partners.

Food delivery platforms began with a genuine promise: access and convenience. They are also the middleman and they also collect the data from customer.

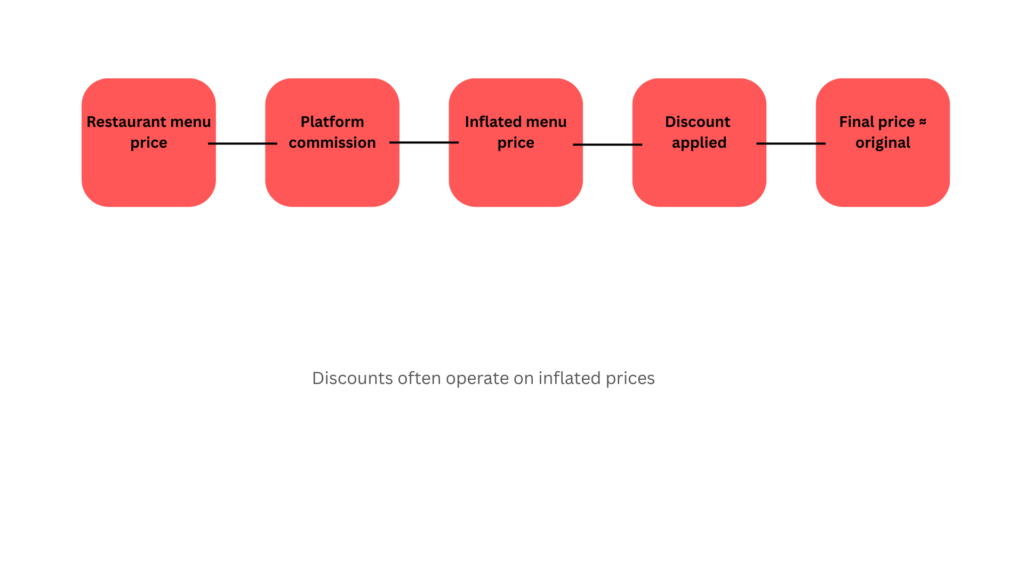

Over time, the structure evolved into something more complicated:

- Platforms charge commissions to restaurants

- Restaurants raise menu prices to survive

- Customers receive “discounts” on already inflated prices

- Bank offers are applied on top, creating an illusion of savings

- Delivery partners still operate under income pressure

What looks like value creation often becomes cost redistribution.

Everyone pays more:

- customers through higher prices,

- sellers through commissions,

- delivery workers through unstable income,

- banks through subsidised offers.

Yet profitability remains thin.

That tells us something important:

The system is expensive to run — not because demand is weak, but because costs are fragmented.

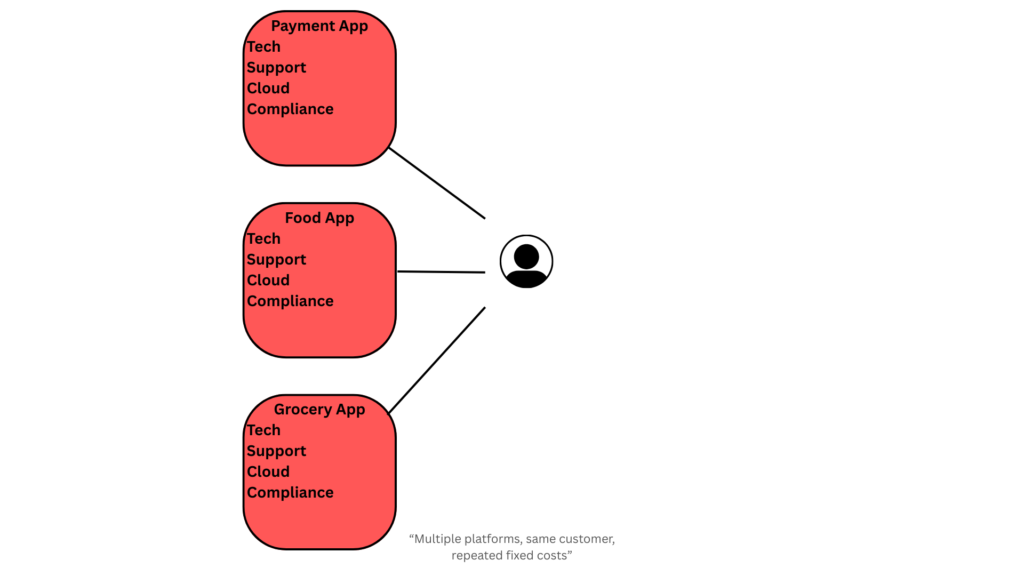

Grocery and quick commerce: the same pattern repeats

Quick commerce follows a similar path:

- heavy infrastructure,

- high operational intensity,

- overlapping technology,

- duplicated customer support,

- duplicated logistics planning.

Again, convenience improves — but efficiency does not always scale in proportion. Here again they are middleman and also collect data.

The common issue

If you look closely, all these platforms are doing something similar:

- collecting data,

- acting as middlemen,

- operating under regulation,

- investing in similar technology like cloud, app development, and maintenance.

Yet all of them charge the same customer separately for what is essentially the same role — being a middleman. This is not a moral problem — it’s a structural one.

I am leaving e-commerce in general because if you will see it is all same but let’s focus on mentioned things only.

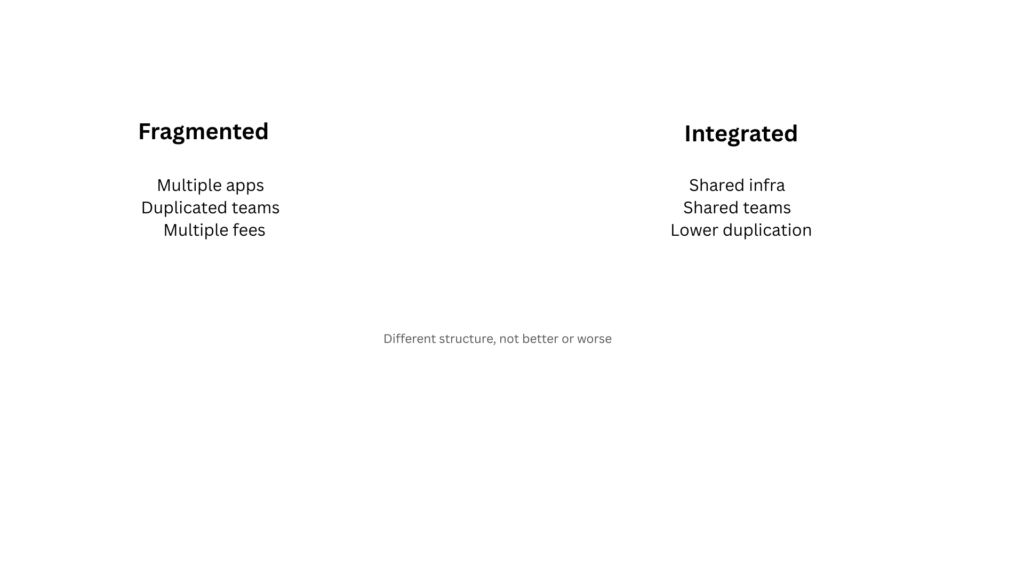

Why mergers and acquisitions come into the picture

This is where mergers, acquisitions, and vertical integration enter the discussion.

Not as a magic fix — but as a response to duplication.

Integration can:

- share fixed costs,

- improve utilisation,

- reduce unnecessary layers,

- stabilise pricing.

But it also introduces real challenges:

- operational complexity,

- regulatory scrutiny,

- workforce transitions,

- cultural integration.

Synergy looks easy in presentations. It’s much harder in practice. This duplication increases cost. And eventually, that cost is passed on to the same customer.

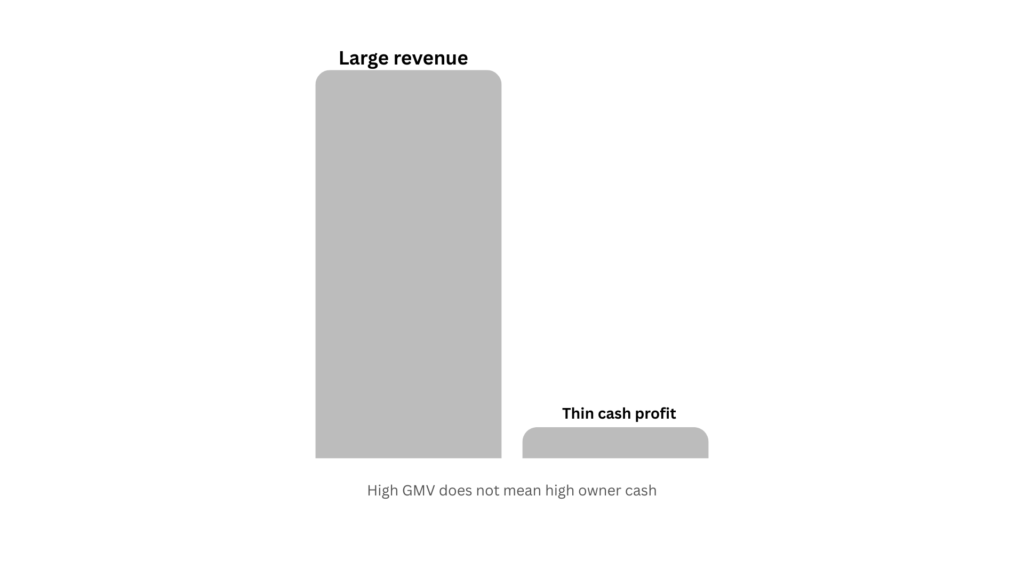

The late-stage problem: when “growth” meets reality

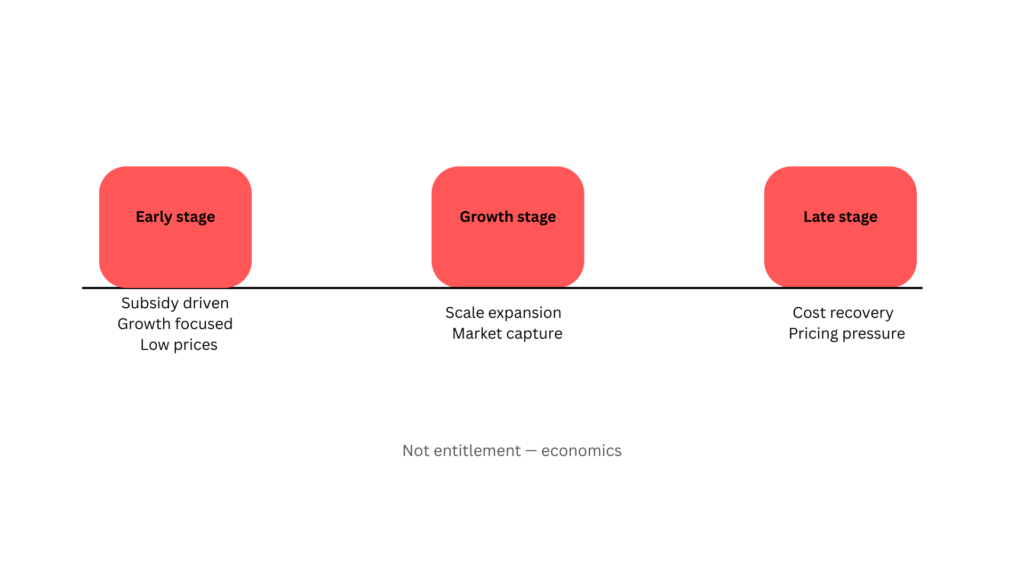

Early-stage platform economics often work because:

- prices are low,

- incentives are subsidised,

- expansion is prioritised.

But when the business moves from early phase to middle or late phase, prices start increasing — not because companies feel entitled, but because they have to cover accumulated costs and investor expectations.

This is why I keep coming back to the idea of knowing your limit. Why chase something that is structurally difficult to sustain?

As Aswath Damodaran often points out in his lecture on Youtube , in fast-moving technology sectors valuation cycle are faster and easier and can achieve high value is short period of time but with that the matureness in company business cycle also comes fast. There is often no strong moat — earlier it was heavy capital investment, today technology lowers barriers.

Jobs, efficiency, and uncomfortable trade-offs

Consolidation often raises fears about employment. Instead of many low-quality, unstable roles, there may be fewer but better-paying and more sustainable roles — along with many indirect jobs created around efficient systems.

Who loses in the current structure? In my view: customers, banks, and employees.

Final thoughts

This is not anti-capitalist article . It is questioning unnecessary expansion and duplication. It is not like that we arguing that these businesses are “good” or “bad”. It is about questioning whether fragmented platforms, all charging separately for essentially similar infrastructure, are sustainable in the long run — especially when customers, sellers, workers, and banks all feel pressure at once.

Maybe the next phase of consumer technology isn’t about adding more layers, but about knowing where enough actually is. Recently, we even see companies changing their names to signal that they are now “large-scale platforms”. That itself shows how the story has shifted from service to scale.

P.S.

. I might be thinking this way because I have ideas about what a different version of this business could look like. Every research and every piece of writing has some objective — and therefore some bias.

I am open to understanding other perspectives and being corrected.

Thanks.